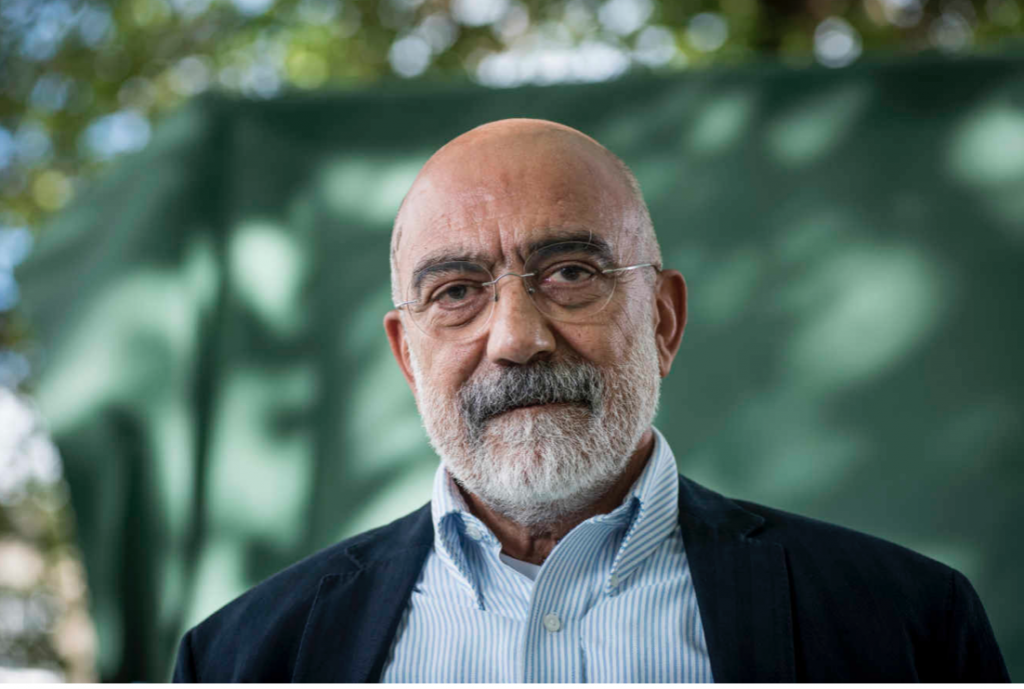

In this exclusive interview published in the weekly newspaper AGOS in December 2025, Ahmet Altan answered questions on his novel O Yıl (That Year), the last decade of the Ottoman Empire and the Armenian Genocide. To read the interview conducted by journalist Nazan Özcan click here: Part One and Part Two.

Ahmet Altan spoke with French journalist Delphine Minoui during a face to face interview at his home in Istanbul. The consequent profile published by Le Figaro on 14 October 2025 can be read here.

In 2020, producer Mary Lynk for the IDEAS program of Canadian Broadcasting Company (CBC) made a documentary about Ahmet Altan’s work and imprisonment, which won an Amnesty International Award in Canada for outstanding human rights reporting.

Mary Lynn also spoke to Ahmet Altan in late December 2023, about fear, resilience, authoritarianism, and the fierce power of literature to inspire a better humanity.

You can read an excerpt from the conversation here or listen to it in its entirety here.

In September 2021, five months after his release from prison, Ahmet Altan was interviewed by Yasemin Çongar at the studio of Kıraathane Istanbul Literature House. In this two-hour conversation (in Turkish) which was webcast on YouTube, the author talked at length about his time behind bars and the three books he wrote in prison, namely his memoir, “I Will Never See the World Again,” and the novels “Lady Life” and “The Dice.”

You can watch the conversation here.

Marc Semo, Le Monde, 09.09.2021

Ecrit pour l’essentiel pendant ses cinq années de détention dans la prison de haute sécurité de Silivri, à l’ouest d’Istanbul, le nouveau roman d’Ahmet Altan, Madame Hayat, est une magnifique histoire d’amour, mais pas seulement. A l’occasion de cette parution, nous avons interviewé (par courriel) l’écrivain et journaliste, toujours dans l’attente d’un nouveau procès après que sa condamnation à dix ans de prison a été annulée en cassation (il était accusé d’avoir soutenu le coup d’Etat militaire manqué de juillet 2016). Il revient ici sur ce roman flamboyant, sur son expérience de la prison et sur ce que signifie être un écrivain au temps de l’arbitraire.

Vous évoquez volontiers « le paradoxe de l’écrivain », toujours libre, même derrière les barreaux, par la force de son imagination. « Madame Hayat », votre nouveau roman, en est-il une preuve ?

Il existe, dans la vie, des formes d’impuissance physique irréductibles. La prison en est une. On vous met dans une cellule et on referme la porte. On vous jette hors de la vie. Vous en êtes exclu, mais en plus humilié par des gens sans foi ni loi qui vous disent : « Tu n’es rien, on peut te faire ce qu’on veut. » Physiquement parlant, vous ne pouvez pas répondre à ce rejet en dehors de la vie, à l’éloignement des êtres chers, au fait concret et à l’humiliation morale d’être enfermé dans une cage comme un animal. Vous êtes prisonnier de l’impuissance. Néanmoins je crois que l’impuissance n’est jamais totale, même dans les pires conditions. Nous avons ce pouvoir d’imaginer qui résiste aux souillures, aux restrictions, à l’enfermement. Pouvoir peut-être plus développé chez les écrivains. Après tout, transformer la chose imaginée, inexistante, en chose réelle, existante, c’est leur travail. C’est une sorte de schizophrénie. Voilà ce qui vous sauve, en prison. Pendant presque cinq ans, j’ai vécu par l’imagination en ignorant la réalité carcérale qu’on m’imposait. Dès que j’en avais envie, je m’imaginais hors de prison. Dès que j’en avais envie, par l’imagination encore, j’invitais les êtres de mon choix à me rejoindre en prison. C’est ce qui m’a permis à la fois de résister à la prison et d’en sortir avec trois livres, tous imaginés depuis ma cellule.

(Click the link to keep reading)

Laure Marchand, NouvelObs, 15.09.2019

Opposant au président Erdogan, l’écrivain turc Ahmet Altan, 69 ans, condamné à la prison à vie, va être rejugé le 8 octobre. Depuis sa cellule, il a pu nous faire passer quelques notes…

Ahmet Altan nous donne de ses nouvelles : « En prison, l’été est la saison la plus dure. On ne peut pas faire grand-chose contre la chaleur. » Pas un mot superflu, pas une plainte. Et pourtant, enfermé avec deux codétenus dans une cellule de six pas de long et quatre de large, l’écrivain turc termine son troisième été dans la sinistre prison de Silivri, à 70 kilomètres d’Istanbul.

Combien d’étés y passera-t-il encore ? Comme des milliers d’opposants à Recep Tayyip Erdogan, cet intellectuel a été arrêté dans la foulée du coup d’Etat raté en 2016. Il a été condamné à la prison à vie pour tentative de renversement de l’ordre constitutionnel. En juillet, la Cour suprême a invalidé sa peine. Mais en l’absence de fonctionnement de l’Etat de droit dans son pays, Ahmet Altan, 69 ans, tient à distance cette lueur de liberté qui s’est allumée au loin. Il nous dit s’être résolu à la possibilité de mourir en prison. Cette « acceptation » lui permet de « se tenir dans l’obscurité avec plus d’assurance ».

Wendy Smith / Publishers’ Weekly, 05. 09. 2019

Last February, Turkish journalist and novelist Ahmet Altan and five co-defendants were sentenced to life imprisonment for their alleged involvement in a 2016 coup attempt. Although Turkey’s supreme court had ruled that “no one could be arrested based on such evidence,” prosecutors insisted that the defendants had sent “subliminal messages” urging the overthrow of the government via television appearance and newspaper columns, and a panel of three judges agreed. An international outcry greeted this blatant violation of human rights and freedom of the press, including protests from PEN and Turkish Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk.

Publisher Sandro Ferri, cofounder of Edizioni E/O in Italy and the English-language Europa Editions (based in New York and London) signed a deal with the jailed author to publish in Italian and English (translated from their original Turkish) Altan’s series of historical novels known as the Ottoman Quartet. (Ferri will also sell translation rights in other languages.) The first volume, Like a Sword Wound, will be released by Europa in October; Love in the Days of Rebellion will follow in fall 2019. The third novel, Dying is Easier than Loving, is not yet scheduled, and Altan is working on the untitled final volume in Silivri Prison outside Istanbul. The writer responded from there to my questions with a wide-ranging commentary on his work, his life, and his future.

“I have never met Sandro Ferri, but he has shown me great friendship for this entire period,” Altan says. “He has always been supportive, and not only by publishing my novels.” (Endgame, Altan’s English-language debut, was released by Europa in 2017.) “While my defense statements have been translated into several languages, they were published as a book only in Italy.”

Although he is better known in the West as a crusading journalist, in his native land Altan has been a bestselling novelist and essayist since the 1980s. Endgame, published in Turkish in 2013, marked his return to fiction after a reluctant five-year hiatus. “When you live in a country like Turkey, you occasionally find yourself having to choose between writing novels and joining those who seek a solution that will end the suffering of the people,” he explains. “It is not very easy to turn your back to people’s suffering; that’s why you are obliged to do journalism sometimes. I am the happiest when I am writing novels. If it were possible, I would write novels non-stop.”

Continue reading “From Prison, Ahmet Altan Confronts Turkey’s Dark History”Lluís Miquel Hurtado, El Mundo, 18.10.2018

Amanece, llaman a la puerta, es la Policía antiterrorista. La siguiente escena ocurre en comisaría: frialdad, órdenes abruptas y para dentro del calabozo. Encerrado junto a individuos «con sus barbas cada vez más largas, sus ojos cansados, sus pies desnudos y sus cuerpos sudorosos, que habían derretido los límites de su existencia y se habían convertido en una gran masa de vísceras en movimiento», según Ahmet Altan (Ankara, 1950), uno de los más de 70 periodistas que hoy duermen entre rejas en Turquía, uno de los países que más informadores encarcela.

La narración angustiosa de lo que el escritor describe como su muerte en vida acaba haciendo bola en la garganta del lector de Nunca volveré a ver el mundo: textos desde la cárcel, que llega a las librerías este jueves (Editorial Debate). Un manuscrito que ve la luz fintando el veto a comunicarse por escrito con el exterior impuesto a Altan en Silivri, la infame prisión tracia que alberga a políticos e intelectuales víctimas de la caza de brujas desatada en las postrimerías del golpe de Estado fallido del 15 de julio de 2016.

On the publication of ”Scrittore e Assassino” in Italy, La Stampa reporter Marta Ottaviani interviewed Ahmet Altan. Banned from all written communication with the outside world, Altan responded to Ottaviani’s questions orally during his weekly one-hour visit with his lawyers at the Silivri Prison Number 9. Here is the full text of the interview in Italian.

La Stampa – Tuttolibri / 28 January, 2017 Rome

Ahmet Altan si trova dietro le sbarre da quattro mesi senza che gli sia stata formulata un’accusa precisa, solo quella di aver mandato «messaggi subliminali» prima del fallito golpe dello scorso 15 luglio. Un motivo per il quale, in Turchia, sono finite in prigione o hanno perso il posto di lavoro migliaia di persone. TuttoLibri è riuscito a raggiungere Ahmet Altan nel carcere dove è rinchiuso tramite i suoi avvocati.

Continue reading ““Non so che ne sarà di me, scrivere mi dà speranza””

Ahmet Altan: The government of this country has always chasing artists. Today, they do the same thing in a more violent manner. Because the current administration does not only hate art but also fears it.

Interviewed by Özlem Karahan. Published by K24 on 15 October 2015. Turkish version of the interview can be viewed here.

Ahmet Altan: Taking sides handicaps writing. Makes you get away from the truth. If you favor one of your characters over others, it doesn’t work. I am the God of my own book. And I have to be as good and as bad as God.

Interviewed by Feridun Andaç. Published in Cumhuriyet on 28 August 2015. Andaç’s analysis of the first three volumes of the Ottoman Quartet and his interview with Ahmet Altan can be read here in Turkish.

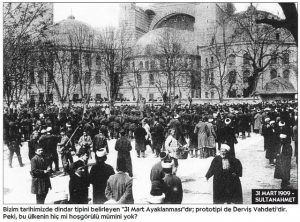

,

,

Ahmet Altan: I want to dedicate all my time to writing novels. I love writing novels. Your asking me if I will go back to journalism is like a man interrupting me as I am making love to ask me to push a cart. No, I don’t want to push the cart. I love making love, damn it! A novelist should not become a journalist. Any society that forces a novelist to become a journalist is a society with handicaps.

Çınar Oskay interviewed Ahmet Altan in March 2015 to discuss his then-recently published novel Ölmek Kolaydır Sevmekten. The interview, which also focused on the day’s political issues and Altan’s journalistic career was published in Hürriyet‘s Sunday supplement. The full text can be read here in Turkish.

Ahmet Altan: You begin each new novel with the same excitement, with the same desire, with the same pain, with the same fears, with the same sleeplessness, with the same tormentations, with the same self-bashing. One moment you say, ”Who am I? Nothing. I don’t exist. I’m not a writer.” A few minutes later, ”I am magnificient. There’s no one like me. I am out of this world. Who can write like this?” You live like a madman.

Moderated by Çiğdem Mater, this conversation with Ahmet Altan took place at the Mithat Alam Film Center of the Bosphorous University in Istanbul. The full text is here in Turkish.