Nothing is scarier than an encounter with the horrifying power of someone who holds your fate in his hands. That person can kill you, lock you up, send you into exile or let you go free. Regardless of the difference in outcome, to be locked up or released by such an authority is equally devastating. You don’t have a say in what happens. People with such authority usually wear a robe and sit on a dais. They are called judges. You can forgive the wielding of such superhuman powers if they are used righteously. What happens, then, if the authority in question doesn’t care about righteousness?

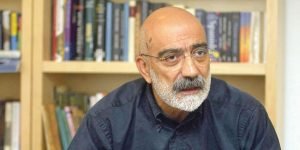

In A Farewell to Arms there is a scene where Hemingway describes a trial of soldiers by military judges that takes place in a cave at the time of defeat for the Italian army. Confident that their decisions will never affect their own destiny, the judges nonchalantly condemn people to death, then put on their caps and salute. They turn people over to the execution squad. During my long incarceration, I faced judges on many occasions. They didn’t even listen to what I said. I laid out the proofs of my innocence and they kept repeating the same accusations. First, they sentenced me to life without parole, then they changed my sentence to 10 and a half years and I was released. I write this as I await the decision a judge will make on the appeal of the prosecutor who objected to my release – they may send me back to prison.

I heard I was sentenced to life and then that I was free to leave prison, all at different times, from the mouth of the same judge. The decision to release me had the same suffocating effect as the one to give me a life term. I knew I was being let go by someone who should not have the authority to make decisions for me.

I am out of the Turkish prison but thousands of innocent people are still there. For over three years, I lived in a small cell with two other inmates who had committed no crime. Nobody listened to what they said. Despite pleading innocence again and again they were condemned to prison by judges not unlike those in A Farewell to Arms.

One of my cellmates is the same age as my son; he was newly married when they arrested him. He is religious but also interested in philosophy and science. He is amazing with his hands, making the most unlikely things with the most unlikely materials. He can turn bags of salt into dumbbells, forks into clothes pins, teaspoons into tweezers. He mixes ingredients into prison meals to invent new dishes. His name is Selman. He believes complaining is akin to arguing against God’s will and he never complains. He never has visitors. He doesn’t complain about that either.

One day, as I was writing my novel Lady Life on the plastic table, I heard music in the courtyard. The sound of a flute. I stepped out. Selman had leaned his back against the wall, closed his eyes and was playing a flute. Noises in the surrounding cells died down. Everyone listened to this unexpected music. Once the song Selman played was over, there was a loud clatter. Pieces of candy bought at the prison commissary were being thrown into our courtyard and a request for an encore. Selman played for hours.

After the courtyard door was locked I asked him where he found that flute. He had made it using the cardboard pages of a calendar. Lacking a measuring tape he had to estimate the distance between each hole; he turned the top of a plastic bottle into the mouthpiece.

No other instrument on Earth could match the sound of that flute. It had a strange tone, a low pitch. Selman never missed a note. He didn’t only play ballads, he played happy tunes too, but now and again his flute would shift towards sorrow.

I was released from the prison one midnight and asked how I was. People wanted to hear the joy a person felt in his first moment of freedom after years. I said I was a bit sad. I had left behind thousands of innocent people, including Selman. I lacked the power to save them and nobody listened to what they said. Not only the judges but a very large part of society has turned into those men in the cave, perfunctorily sentencing others to death. They put on their caps, salute, send the person off to face the execution squad and turn to their next victim.

Once you have seen that cave, witnessed the suffering of innocent people and once you have listened to the cardboard flute, you can’t possibly be ecstatic about leaving prison. You feel like an accessory to a terrible crime. As a prisoner, you are the victim of injustice; once you leave, you become an accomplice.

I know that the most frightening thing on Earth is an encounter with someone who holds the power to determine your fate. I know what torment and humiliation it is that the person with that authority doesn’t care about what you say. I know the sound of a flute can express unquenched longing.

I also know it is possible that they will rearrest me. But Selman is already under arrest. He is my son’s age, he makes dumbbells from salt. He has no visitors. He never complains. He just leans against the wall and plays his flute.

This article was translated by Yasemin Çongar.